Louise Jones, PhD, MEd Director of Research & Scholarly Activity

Mentoring

Mentoring, according to Lois Zachary, author of the 2021 edition of The Mentor’s Guide, is primarily about relational engagement between mentor and mentee. Zachary quotes the old African proverb as a means of describing the essence of mentoring:

“If you want to travel fast, travel alone; if you want to travel far, travel together.”

Graduate Medical Education represents the culmination of many years of study and seeks to equip resident physicians with a broad range of competencies as well as supporting their capacity to be evidence-based practitioners. I think that any medical residency program would come under the “travel far” category! In fact, emerging research suggests that the resident’s support systems have a much larger impact on their program completion, board certification success, and mental health than was previously thought. Mentoring represents an explicit support mechanism put in place for a variety of reasons.

Over the next several weeks, we will explore the many facets of mentoring and the goals of these important relationships. Let’s get started!

What are the different types of mentoring in graduate medical education (GME)?

GME educators have a lot of different roles, Hardin and Crosby suggest that the medical educator juggles 12 specific roles, grouped into six areas! That is a lot of skillful juggling. It may surprise you to know, but there is very little formal training in each of these roles. Physician-educators tend to be subject matter experts in their discipline and then add the educator skills as they progress in their academic careers.

The activity of facilitating growth and learning represents a large proportion of the current approach to residency programs in the United States. Our clinical educators facilitate learning and skills acquisition during clinical case teaching, content specific teaching, and formal mentoring relationships. Some people call this the quasi-apprentice approach, or situated learning. It’s at this early stage of physician learning that the mentor/model is critical. It develops not only medical knowledge and skills, but team leadership skills, patient relationship skills, professional identity development, evaluation and assessment roles, as well as curriculum planning. There are recognized generic mentoring roles and very specific, often time-limited mentoring relationships that we typically see in robust graduate medical programs.

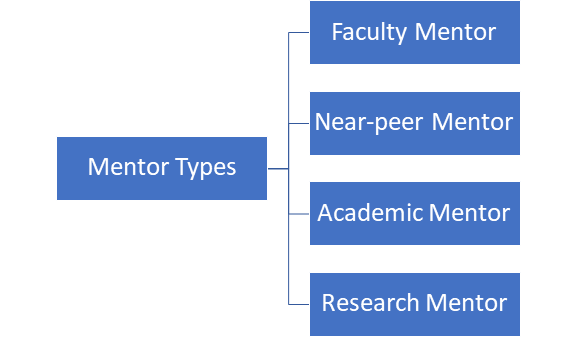

Here is a simple chart of some typical mentoring opportunities we see in our programs at Northeast Georgia Medical Center (NGMC):

Next blog post, we will dive deeper into exploring these different types of mentors – until then!

To learn more about our residency programs, visit ngmcgme.org.